Allen C. Guelzo on Robert E. Lee

Mention the name Robert E. Lee today, and you may meet with shouts of denunciation. The statues that bear his image around the U.S. have faced increasing scrutiny, defacing, and removal. Why is that happening particularly in today’s climate? And why has Lee, the primary military officer who led the rebellion in the American Civil War, enjoyed a typically more venerated legacy for so long? What are we to make of this general of the Army of Northern Virginia, who fought tenaciously for the Confederacy and the defense of slavery yet made decisions—especially the decision to surrender to Ulysses S. Grant rather than protract the war—that ultimately helped bring the Union back together?

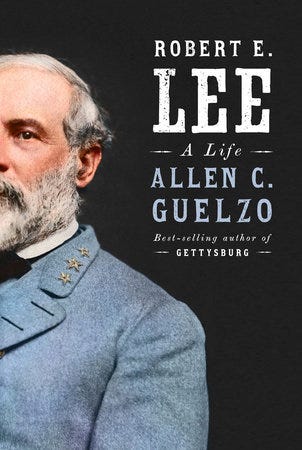

Respected historian Allen C. Guelzo addresses these and many other questions in his recently published biography, Robert E. Lee: A Life (Knopf, 2021). Guelzo, Senior Research Scholar at the Council of Humanities at Princeton University, has written several books on the Civil War and Reconstruction era in America, including the Lincoln Prize–winning Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President (which I reviewed here), Gettysburg: The Last Invasion (which I consider here), and Reconstruction: A Concise History. Now he has turned his gaze south to consider the life and times of Lee, and given the current context of questions swirling about Lee’s legacy, Robert E. Lee is perhaps as relevant as ever.

I want to state at the outset that Guelzo does not write a hagiography. That isn’t his goal. Rather, his aim is to provide historical analysis, and he completes the work of historiography necessary to do this well.

One of the helpful aspects of Guelzo’s book is his illumination of Lee’s family history, childhood, and early adult life. Growing up as the son of Revolutionary War hero “Light-horse” Harry Lee was no easy task, especially since his father turned out to be not so successful in his later years and not very present for Robert—both because of his roaming and because of his death in 1818, when Robert was only eleven. His erratic father’s illusory search for better financial investments led to a yearning in Robert for security, something that he felt nearly always eluded him. And yet, as Guelzo insightfully points out, Robert E. Lee was marked not only by a search for security but also by a search for independence, and it was this tension that explains many of the important decisions that marked his life.

Of all the decisions Lee made, most significant for him and the history of the United States were Lee’s decisions to decline an offer to lead the army of the North, to resign his commission in the army, and to accept a commission as head of the army of Virginia—all of which happened in the course of about three days. The popular line is that Lee was committed to his state of Virginia above all. Guelzo treats this topic at length and makes a compelling argument that this popular line of thinking doesn’t do justice to several details in Lee’s life.

Of significance is that Lee didn’t own land in Virginia and that he lived much of his adult life in army commissions in other parts of the country, including New York and Texas. Arlington was his home but only by marriage. Arlington was the home of his wife’s father, George Washington Parke Custis. Lee’s father-in-law died only shortly before the election of Lincoln, and Lee was cut out of the will. But while he himself didn’t receive anything in the estate, his children did—and Lee was made the executor of the will. His job was to ensure that the estate would be profitable enough that his children would receive an inheritance.

Fascinatingly, Lee’s Arlington wasn’t even part of Virginia at the time of secession; it was part of Washington, DC. In his letters from that period, one can see that Lee’s ultimate devotion was to his children, protecting their future livelihoods. That was the “Virginia” he felt devoted to—that and the network of extended family to which he felt obligated. His decision was driven in large part by a desire to preserve his family’s future—a move based on a yearning for security.

As for slavery, Lee said he was opposed to the spread of the institution and claimed that he would give up all the slaves in the South if he could avoid war and maintain union. But his family came first, and that is perhaps the best driving motivation for why he devoted himself to the defense of what he considered to be a constitutionally questionable government whose aim was to perpetuate and spread the institution of chattel slavery, an institution he expected to fade away—though he did little in the way of action to bring it to an end.

So in many ways, this decision reflected the security-independence tension in his life. He sought to protect the security of his family and their future by standing with the network of extended family that provided a safety net of sorts for him and his children. Lee suffered from feelings of failure in paving an independent path throughout his life, but though he genuinely desired independence, his desire for security often held him back from taking the risks needed to pursue it.

Guelzo weaves this fascinating theme throughout his book, and he fleshes out the theme further when he suggests that Lee’s final years as the president of Washington College (later, renamed Washington and Lee University to honor him) were perhaps the time when Lee asserted his independence most forcefully. That simple observation is one piece of evidence showing that Guelzo weaves a cohesive narrative from Lee’s birth to death—and really from Lee’s ancestors to his legacy in our own day.

In the epilogue to the book, Guelzo offers masterful analysis of the “glory” and “crime” of Lee—not only in his nineteenth-century context but also in our twenty-first-century context. His analysis reaches to the recent movements to topple Lee statues, and he considers the charge behind those efforts—white supremacy—vis-à-vis what he considers the ultimate crime of Lee—treason. And he also fruitfully explores the reasons why the former charge resonates more in our day than the latter. (You must read this section before passing judgment.)

Though reading a biography of Lee may seem counterintuitive in a day when his glory has been called into question, perhaps there is no better time to consider the life of Robert E. Lee, the contradictions of his consequential decisions, the mixed legacy he leaves behind him, and how we can understand our own day in clearer light with reflection on the meaning of the past. And as usual, Guelzo proves a gifted guide in this exploration.