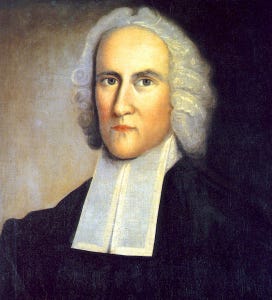

Jonathan Edwards as Mentor

When we think about Jonathan Edwards as a pastor, we tend to conjure up a fairly negative picture: a lackluster preacher and bookworm who preferred spending as much as thirteen hours per day in his study over mingling with his congregants—a group of people who ultimately ousted him from his pastoral post in Northampton.

Rhys Bezzant does us the favor of offering a corrective to Edwards’ reputation as a pastor in his article “‘Singly, Particularly, Closely’: Edwards as Mentor” [Jonathan Edwards Studies 4, no. 2 (2014): 228–246]. He contends that “Edwards was actually a very skilled mentor and expert trainer of leaders for the church” (229). And he offers incisive recommendations for the church to learn from Edwards’ mentoring style today.

Despite Edwards’ social inadequacies, he was actually deeply concerned for the state of his people, often spending hours with parishioners in his office offering spiritual counseling (though he avoided visiting them in their own homes). Also, while he was no George Whitefield, Edwards was a more engaging preacher than the common caricature of the New England divine suggests. What Bezzant highlights is that Edwards adeptly prepared new leaders to continue the revivalist movement long after he passed from the scene.

This training generally began in Edwards’ own home, a tradition stemming from the seventeenth century when Puritan pastors taught younger protégés in a personal, familial setting. Essentially, these “schools of the prophets”—as they were called, drawn from 1 Samuel 19 and 2 Kings 2—provided a mentoring relationship for pastors and aspiring ministers. Edwards continued this tradition in his own home, and his students, most importantly Joseph Bellamy and Samuel Hopkins, continued it after him, laying the groundwork and network to spread Edwards’ ideas.

In looking at his practice of mentoring, Bezzant highlights two aspects that made it so effective. First, Edwards practiced a Socratic, dialogical method of teaching that encouraged critical thinking. Second, he adopted the common epistolary practices of his day to strengthen his relationships with students and further the evangelical movement.

Building from his description of Edwards’ mentoring context and practice, Bezzant goes on to offer suggestions for learning from Edwards in pastoral ministry today. He is motivated not simply from an interest to understand Edwards better, but also by “the urgent need for contemporary churches to better exercise leadership development” (230).

What has happened to the art of mentoring? Has the busyness of our modern, technology-driven culture eliminated the ability to mentor students? Bezzant believes there is still hope for exercising effective mentoring in our world today by drawing from church history.

In many ways, Bezzant sees his article as passing on the gift of mentoring that comes down to us from Edwards through his student, confidant, and first biographer, Samuel Hopkins, who preserved much of what we know about Edwards’ mentoring approach. Bezzant makes his study of Edwards directly applicable to the church today by suggesting four ways we can learn from his style of mentoring.

First, in contrast to the professionalization of ministry and the corporate model of the church, Edwards’ mentoring approach calls us to share our own selves. For example, Edwards invited Bellamy “not just into this spiritual world, but into his pecuniary and marital world too” (246). Bellamy learned by watching Edwards in his home and by hearing him share his life experiences through letters in which Edwards relied on Bellamy to help him conduct business. The two were closely linked because Edwards shared himself with Bellamy, something pastors should consider prioritizing today.

Beyond this, Bezzant notes that Edwards highlighted the work of evangelism for his students that helped them set ministry priorities that mirrored his own. He also entrusted the ministry to able students who would continue and spread the movement. And with his Socratic approach to learning, he gave them freedom to develop their ministries beyond strict obeisance to his views—something Bezzant calls “[m]entoring as contribution and not control” (245).

In Bezzant’s view, pastors can benefit from Edwards today by developing close mentoring relationships that both strengthen bonds of affection and effectively continue the spread of the gospel. While Edwards certainly had his flaws in relating with people, he was not quite the inept pastor we sometimes think he was. Rather, Jonathan Edwards’ model of pastoral ministry offers insight for how pastors today can make their legacy outlive their own time on this earth.