The American Frontier, Borders, and the Christian

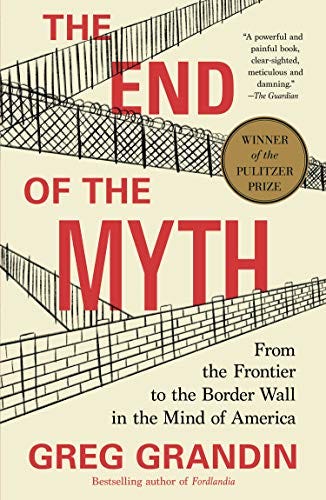

I recently finished listening to Greg Grandin’s The End of the Myth: From the Frontier to the Border Wall in the Mind of America (Metropolitan Books, 2019). He tells an unsettling narrative of how Americans have used space to address some of their nation’s deepest problems, particularly its hang-ups with racism and empire building. The book traverses much ground, and while it is not focused on religious elements of American history, I found that some themes in this 2020 Pulitzer-Prize-winning volume (in general nonfiction) prompted some thoughts regarding American religion worth discussion on this blog.

I won’t try to give an exhaustive account of the book’s many details. The scope is wide, from early America and the beginning of westward expansion in the young republic to the aims of Donald Trump to build a wall along the American border with Mexico. Grandin treats several themes, such as the prevalence of war in American history and its role in the unfolding of the frontier. He attends to racial conflict between whites and other groups, especially Blacks, Native Americans, and Hispanics.

The main thrust of the argument goes something like this: the United States, throughout its history, has continuously seen the frontier as a way to deal with problems within the nation, but with the loss of a frontier, the nation has reversed course and is now seeking to shut others out and focus on self-defense and self-preservation.

For example, the problem of slavery was very much wrapped up with the American West, as North and South vied for political power with the adding of new states. The problem of Native American presence in the eastern states was thought to be easily solved by sending them west (see my review of Jennifer Graber’s Gods of Indian Country). But these problems were never fully resolved by western expansion—as is obvious in the racial unrest that marks our own time.

Another key aspect of the frontier was its function as a “safety valve” of sorts, providing a place for restless souls to let off steam and find their way in the world. That is, the East was happy to send its discontents west to unleash their wild antics. The safety valve, however, was inherently problematic. It was not for all but only for whites; Blacks, Hispanics, and Native Americans all found themselves under duress and facing oppression. It was also problematic in that no one realized that it could only ever function as a short-term release. Eventually, frontier land would run out.

All told, the book is somewhat of a dismal take on American history. I think we can say at least two things: (1) Grandin’s book may be more depressing than the whole story really is. I think it’s clear that Grandin is selecting certain historical elements and quotations to weave a narrative. He doesn’t have space to give a full treatment, for example, of Theodore Roosevelt’s successes and failures; Grandin focuses on how Roosevelt connects to the themes in his book. There are, I think, more hopeful elements in the American story that are omitted—but perhaps omitted largely out of necessity, due to space limitations.

But (2) Grandin rightly reveals some sad realities about the American story, and these shouldn’t be ignored. He shows, for example, the role that racism has played throughout US history. He also details the issue of nativism, which Grandin associates with the conservative right in his narrative. This is troubling, since many evangelical Christians would fall into the conservative political category. And many evangelical Christians have fallen into nativism as well. Perhaps too often, American evangelicals have connected their faith with their political desire to push out people of other nationalities in pursuit of a homogenous “Christian” nation.

This nativism is most clearly visible today in the Republican plank that aims to build a wall with Mexico. Many evangelical Christians have joined this way of thinking for various reasons. While Grandin doesn’t explore this as an evangelical impulse, I would speculate that many evangelicals view the issue from a lens of upholding the rule of law and of defending ourselves from possible terrorists slipping through our lines. In other words, I think most such evangelicals mean well and emphasize these arguments because they make sense, in their minds, religiously and politically.

But Grandin’s account reveals a harsh reality along the border with Mexico that Christians cannot ignore. Interestingly, some Vietnam vets have traveled to the area to sort of patrol the borderlands, continuing the wars from our past in hopes of redeeming them in some way. But the abuse, mistreatment, family separation, and murder of migrants coming from south of the border is a story that I fear too many evangelicals are unaware of, and by supporting right-wing anti-immigration policies, they may be buying into a racist philosophy of violence they wouldn’t support if they understood it. Those who do understand it and support it have no excuse.

At this point, I want to change gears and consider this history from a theological standpoint. The fact is that God’s people, the Israelites, were once wanderers in a desert, and God led them to a new land (see, e.g., Gen. 12:10; 15:13; 21:34; Ex. 6:4). And he also told them to care for and show understanding to the immigrant, or “sojourner.” In Exodus 22:21, God commands Israel, “You shall not wrong a sojourner or oppress him, for you were sojourners in the land of Egypt.” And in Exodus 23:9, God expands the basis for this command: “You shall not oppress a sojourner. You know the heart of a sojourner, for you were sojourners in the land of Egypt.”

Israel’s own history of migration was meant to stir up an understanding for others who undertake such journeying. They could identify with the immigrant, so much that they could admit to “know[ing] the heart” of a sojourner. This kind of Christian teaching reminds us that followers of Christ are called to show compassion to the immigrant, not shut them out. And this clearly applies to Christians as much as it did to ancient Israelites, for we are all the more “sojourners,” traveling through this world toward our final home in the new heavens and new earth. As Peter explains, “Beloved, I urge you as sojourners and exiles to abstain from the passions of the flesh, which wage war against your soul’ (1 Pet. 2:11).

This is not to deny the place for legitimate debate over what an immigration policy should look like for any given nation. Orderly procedures are valuable. But race-based, state-condoned violence should not be countenanced—whether by a nation or by a Christian.

One final thought: a key point that Grandin makes is that frontier proponents failed to recognize the limits of the frontier. Eventually, frontier land would run out, or else it would be translated into an imperial quest. The notion of limitation certainly echoes the teaching of Christian theology that we are finite creatures. And thus, human life is not about conquest in the way it is often cast in American frontier terms.

Rather, recognizing our limitations, Christians are to resist the pursuit of expanding our nation’s geopolitical power and scope, instead seeking to expand the kingdom of God—a kingdom that transcends borders because it permeates the hearts of people, uniting people across racial and national lines into one peaceful body. Christian theology shows that such a vision is no myth; rather, it is hope for people “from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages” (Rev. 7:9). For God is building a new city. And in that new city will be a tree of life, and the leaves of that tree are “for the healing of the nations” (Rev. 22:2).

If this is the vision of how God’s kingdom will ultimately be realized, it ought to shape the Christian approach to questions of nativism, racism, and immigration today. Because we are sojourners in this world, we ought to “know the heart” of other sojourners. It seems that Christians should be marked more for their devotion to “the healing of the nations” than to building walls and keeping the “other” out.